Karagiozis, Greek shadow puppet theater, has a history in Greece that links conceptually with one line of development that goes back to pre-classical times, and with a second, more direct connection, that positions the form in Greece from 1799, the earliest date at which the term shows up in a documented source. Going forward, Karagiozis spawned a comic tradition that served Greece well up to modern times — through epitheorisis, or review performances, Karlos Koun’s theatrical renditions of Karagiozis, and satiric comedy on the stage.*

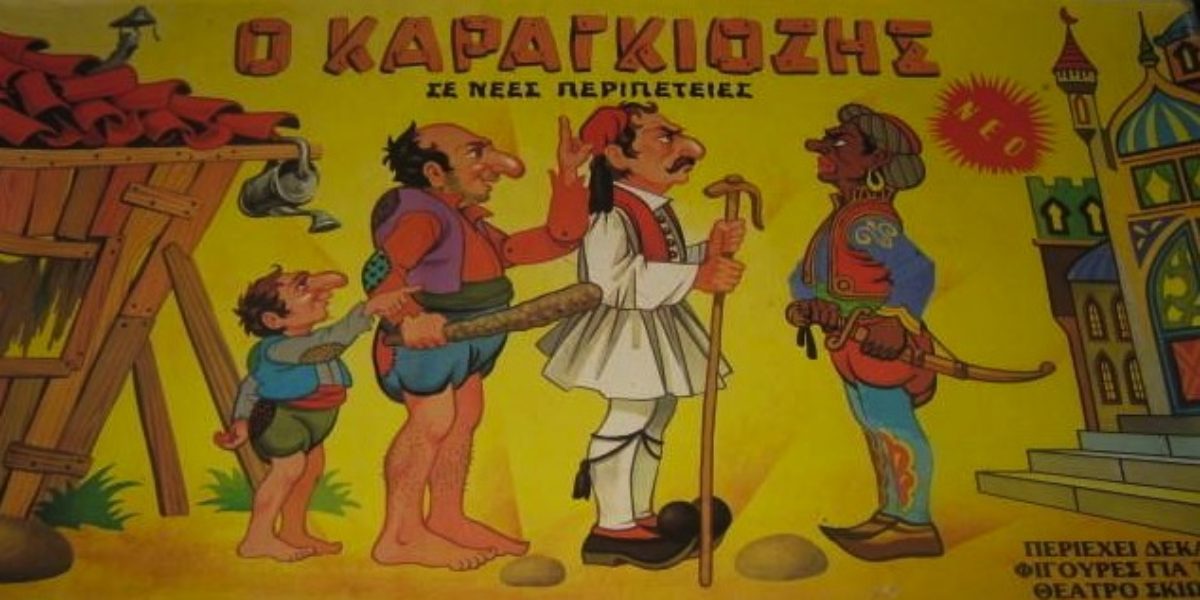

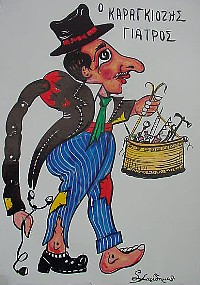

Classicists, theater and drama historians including Allardyce Nicoll, Hermann Reich, Cedric Whitman, Alex Solomos, Athanasios Fotiades, Metin And, and P. Kakridhis have argued for and against a continuity through pre-classical mime, Aristophanes, Commedia dell’Arte, Byzantine mime, and Pulcinella, to the Turkish Karagöz performance and then to the Greek form of that performance, Karagiozis. Their connections include the parade of character types and loose sequences, the anarchic disrespect for authority, both religious and political, identification with the common class and its oppression, the comic statement, stock scenes and coined language, and the bald-headed, hunch-backed, bare-footed, phallophoric anti-hero typology that led to the Karagiozis figure itself and to the Greek performance that bears his name.

Along a more direct and demonstrable route, theater historian Walter Puchner has argued persuasively that Karagiozis originated in the Ottoman Empire, which had spread its power and influence throughout the Middle Eastern territories defined by the boundaries of the empire, and that it arrived in Greece through the Balkan countries from Constantinople. The first reference to the Turkish performance was likely by Evliya Chelebi in the seventeenth century and the first reference in Greek lands was at the very end of the eighteenth, 1799, in Tripolitza (Tripoli), in the Morea, southern Greece, by the Frenchman Francois de Pouqueville. More substantially, an actual performance was viewed by the English traveler John Hobhouse in 1809 in Ioannina, Epirus, in northern Greece.

From its first sighting, Karagiozis had to contend with a reputation that linked it to what in Greek lands was regarded as a vulgar Asiatic influence that was indecent and thereby unfit for women and children. The Greek church and political authorities under King Otto, following Greek Independence from the Ottomans in the War of 1821, censored and even banned the performance well into the last quarter of the nineteenth century, until Karagiozis finally reached its majority in the 1890s. Here, it was regarded by one source as a force of struggle, a new socialism of the Greek people that had infected the nation, Karagiozitis.

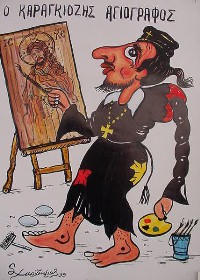

Karagiozis had spread itself across Greece from the provinces to Athens by the 1850s and thereafter made its home in the new capital, where it came to rival all other entertainments. It had faced down the social and moral constraints of the Orthodox Church, which was itself in a struggle to assert itself in Greece, cut off from the Patriarchate in Constantinople and divested of much of its property and former independence. Moreover, Karagiozis had not only competed successfully with a widely popular puppet performance, Fasulis (with its Italian roots in Pulchinello, a form of Punch and Judy show), but, more critically, had undermined the French and Italian theatrical troupes sponsored by the King and his followers in Athens. As Greek theatrical troupes developed in the capital, Karagiozis would outpace them as well, making it the most highly favored of theatrical performances among common Greeks. Karagiozis had championed the lower classes, won the favor of a developing middle class, and, by adapting itself to dramatic, heroic, and historical themes like those found in the theater, found a new tolerance among the upper reaches of new Greece. To find its place, Karagiozis had to break away from its Turkish roots and accept a more national role as a Greek performance. It absorbed Hellenic influence, tied itself more closely to laic attitudes and Christian values, and effectively overlay its Romaic expression with a Hellenic face.

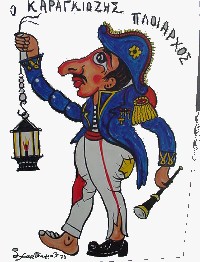

In sum, Karagiozis would profit from at least three favorable historical winds that blew in its favor. The first was the criticism leveled against the performance by the upper classes, the political elite, and the church, which forced it to adapt by minimizing the grossness of its themes, controlling the primitive anarchy of the performance, and achieving a more culturally appealing kind of satirical comedy. Second, it profited from a folk-life renaissance in late nineteenth-early twentieth century Greece that acknowledged its value as a laic expression and ensured its survival in the face of the growing strength of live theater and the coming of the cinema in the twentieth century. Finally, as a form of national theater and capitalizing on a regenerated historical sense during the Greek border wars of 1899 and 1912, Karagiozis’ demographic and geographical reach would prove a potent instrument in reinforcing and exploiting the patriotic fervor of the common Greek.

* For more on the modern connections, see Gonda Van Steen, Cassas Chair in Greek Studies, University of Florida, and author of Venom in Verse: Aristophanes in Modern Greece; and Stratos Constantinidis, Center for Slavic and East European Studies, Ohio State University, author of Modern Greece in a Quest for Hellenism.

Linda Myrsiades, Emeritus Professor of English and Comparative Literature, West Chester University. For the HFC.