Folk Songs have been the most highly appreciated form of oral tradition both in Greece and throughout the rest of Europe. They first became known during the years of the Greek Struggle for Independence: it was around 1824 – 1825 that one of the great French scholars, Claude Fauriel, published a two – volume collection of folk –songs with an extremely interesting introduction and poetic translations in prose. This publication made an impression on European scholarly circles and was immediately translated into German (twice in 1825), into English (also in 1825 and into Russian. Writers like Stendhal and Goethe were thrilled – the latter even translated a few of the texts for his own periodical ‘Kunst und Alterthum’ in 1827. There followed a score of anthologies, initially by Europeans, as for instance by Niccolo Tommaseo (in 1843, with an accompanying translation in Italian), and later by Greek anthologists.

The Greek rural community was then essentially isolated and static, having a poor income and little education. Life and agricultural work proceeded at an extremely low pace – indeed, almost at a standstill. These characteristics played a determining role in the composition of folk songs: themes, expressions and human types were the creations of a poor, inflexible and virtually immobile population. The frugality of expression of the folk-song its elemental imaginative scope can be directly correlated with the circumscribed rural reality of the time.

Poetic tools such as themes and images are also limited. When the singer wants to describe a handsome youth, he frequently uses typical stereotype imagery.

He was so tall, he was so slim, he had such arched eyebrows,

or ‘laced eyebrows’, or something similar – in other words, variations of the same portrait, be it about the proud young son of a rich family or the humble son who has left his mother to seek his fortune abroad. Whenever the heroine must shine with beauty, as in the ballad of ‘The Maid of Honour who Became a Bride’, or in ‘The Two Brothers and the Bad Woman’ the stereotype recurs again:

She lets the sun shine upon her face

The moon upon her breast

The raven’s plume upon her brow like lace.

Nevertheless, this frugality of means and expressive modes led to a significant poetic tradition; Greek folk songs are distinguished by an intense dramatic character, which succeeds in satisfying even our modern aesthetic criteria. This refinement over the ages has resulted in verse that is devoid of everything superfluous and yet at the same time is both poetic and charming.

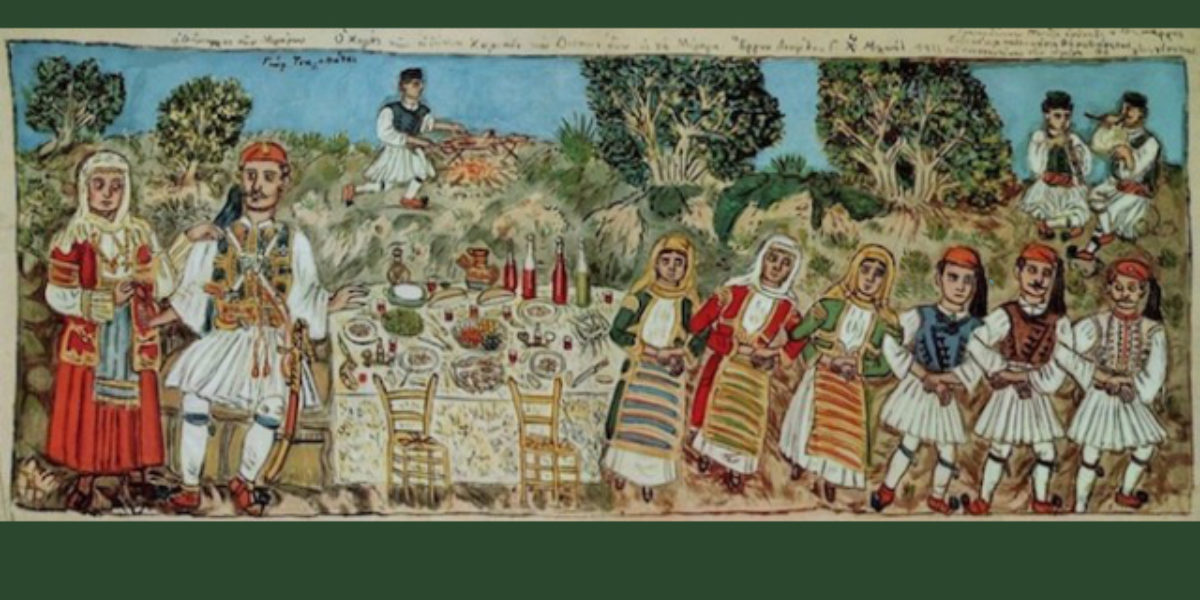

Although folk songs are closely associated with the rural world, they do not expressly portray the harsh realities of this world. In their context we find none of the actual daily problems experienced by farmers, such as hunger, fear, taxation, suppression, or even direct and raw violence. Instead we encounter a world of grandeur and wealth, peopled by rulers and princesses, well-to-do families with many children, tall and slender young girls. We see a world where garments are always made of gold, silk or velvet, where herds of cattle are huge and rams wear bells of silver, where horses are black and fleet of hoof, and where the threshing – floor is always made of marble. A world of intangible desire, coveted and longed for, with no allusion whatsoever to the dire circumstances of daily life.

Mother with yout nine sons and with your only daughter

At night you bathed her and you tied her ribbons in the Pale light

Of the sweet moon

Now that they’ve sent from Babylon

To ask for her as a bride

Or

A pedlar’s coming down the slopes

Leading twelve mules and fifteen she-mules,

or

Leading twelve mules laden with silver,

Or else

The Golden-hoofed hinny carries the young master.

Even at the tombstone is:

A stone of gold, a stone of silver, a stone gilded and golden.

Of all the pangs of life only the two extreme ones are mentioned, being away from the homeland and death. Yet even then the affair is described in a most realistic way:

Charon’s unfair. He is a shrouded pirate

Or

Hark to what Charon’s mother spoke:

Those who have children, let them hide them,

And those who have siblings, harbor them,

Let wives of worthy men conceal the men,

For Charon’s grooming himself now to come out and steal.

There is nothing metaphysical , only scenes of real death: pirates storming the villages and people running to hide. The picture has its roots in reality and, on top of that, Charon’s mother, like the mother of a common murderer, is sorry for her son’s victims and does her best at least to reduce their number.

The world of folk songs is therefore neither the real world, nor a transcendental one. It depicts a down-to-earth reality that is nevertheless elevated up to an ideal plane. The metaphysical notion of Christian religion is absent, as is any other metaphysical concept. Even death itself is but a loss, the loss of life and nothing more. It is this aspect of folk songs that grants them their poetic value.

The oldest group of songs that may be dated by the social circumstances they reflect, must have appeared about 1000 AD. They are called Akritika, that is, songs referring to the legendary class of warriors, the akrites, or frontiersmen. They describe the clashes between the powerful local rulers of Asia Minor with the central administration of the Byzantine Empire. Even though the emperors were the eventual winners of these battles, the songs extol the prowess of the local rulers because they were composed in their small courts.

The next group of songs has distinctly more urban character and must have composed mainly in the islands, on Crete and in coastal towns, in form that has reached us through oral tradition, between the late 15th and early 17th centuries. It is believed, though, that the themes of this group originate in a far earlier time. This group includes short ballads about the basic dramas of daily life: the faithless wife of the husband absent in a distant island, the unlucky bride, the mother who kills her own child to conceal her adultery, erotic rivalry, the human sacrifice involved in building a bridge, even returning from the Underworld.

The next significant group of songs is the cycle known as Klephtika, about the deeds of the Klephtes, or guerrilla revolutionaries, who opposed Ottoman rule. These songs were composed between the mid 18th century and about 1821.

Songs referring to everyday events cannot be classified. Some themes are definitely very old, while others can be traced to more recent times. Poetically, the most important ones are the songs of lamentation. Next, come the Christmas and New Year carols, the wedding songs, love songs, lullabies, single couplets, and so on. Indeed there was no important event that was not sung about and no daily activity that was not accompanied by song, As William Leake, one of the most reliable observers of the Greek region, wrote in 1814: “The Greek make ballads and songs upon all subjects and occasions.”

Alexis Politis, reprinted from Greece: Books and Writers, courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.