“O land of Byzantium, o thrice blessed city, thou center of the earth, jewel of the universe, far-beaming star, lamp of the nether world … ”

Konstantinos Manasses: “Οδοιπορικόν” (12th century)

Constantinople, the capital of an ecumenical empire, was the Imperial City where the Emperor of the Romans, as well as the ecumenical patriarch, had his seat. It was the heart and the symbol of the empire and its fall marked its end.

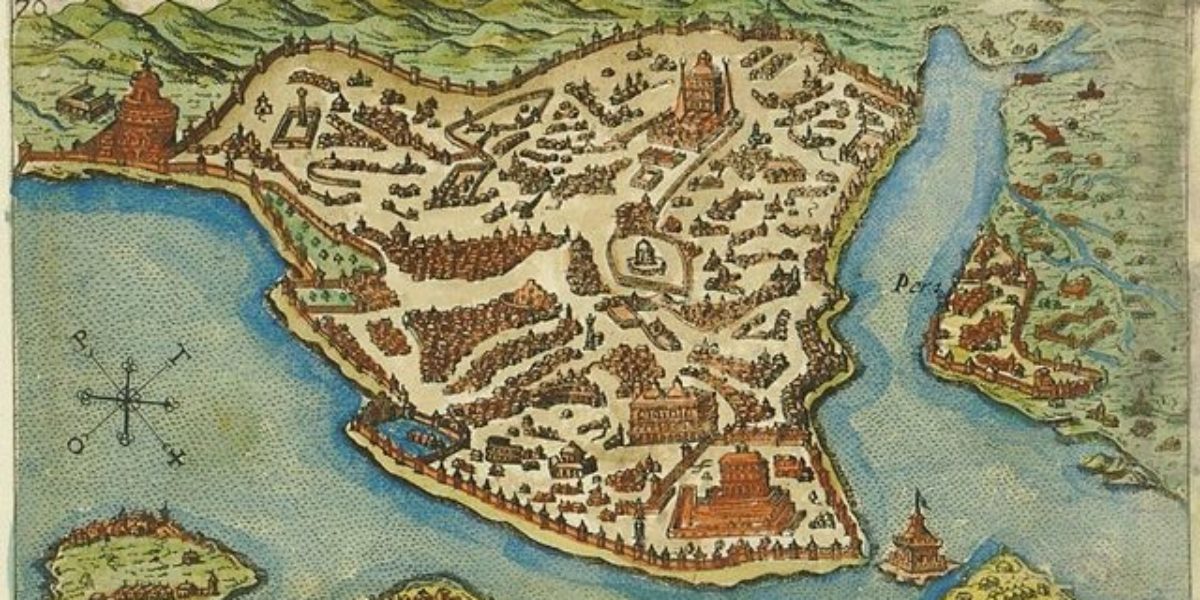

The city’s origin is traced to Greek antiquity, when, according to legend, Byzas from Megara founded it in the 7th century BC. The Roman emperor Septimius Severus restored it and the first Christian emperor, Constantine, inaugurated the New Rome on 11 May 330.

The architects Constantine hired maintained the old center while enlarging the urban space. A new avenue was constructed, the famous Mese Odos (Middle Street), with shops on the right and left and various public spaces such as the circular market, the forum of Constantine. The hippodrome was expanded and the “Great Palace” was built as well as walls that protected the city on the inland side and Christian churches. Constantine adorned the capital with ancient statues that he took from the Greek cities further east, turning the city into a veritable museum.

Very soon the population increased, creating the need for new walls and a new port, which were constructed in the 5th century, under Theodosius. However, the emperor, who left his indelible mark on the City, was undoubtedly Justinian. The most important of the churches he built are the church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, the church of Saint Irine and the masterpiece of Byzantine architecture, Hagia Sophia.

The first walls of the city were built by Constantine the Great , but as the city rapidly grew, the need arose for new defensive walls. The fortification works were completed in 447 under Theodosios II and were built as double walls with a trench between them. The width of the trench ranged from 15 to 20 meters, and on its exterior expanse rose the smaller wall, which was 2 meters wide and 8.5 meters high, outfitted with 70 watch towers.

The Theodosian Wall is the greatest example of Byzantine defensive works and protected the royal city for about 1000 years, rightfully earning the nickname “God-protected (theofylakta) walls.”

In 542 the city was hit by bubonic plague and lost one third of its population. The centuries that followed (7th-9th) were called “dark,” because the capital city went through tough sieges by Persians, Avars, Bulgars and Russians, while also facing internal conflicts, earthquakes, and epidemics.

The end of the rule of the Iconoclasts and the restoration of Orthodoxy mark the end of the dark centuries. From then on there is an intellectual and cultural rebirth that extends to the Christian Slavs as well – Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs. The Imperial University, Πανδιδακτήριον, founded in 425, was overhauled, relocated to the precincts of the Palace and renamed Πανδιδακτήριον της Μαγναύρας – University of Magnaura. Medicine, law, rhetoric and philosophy with emphasis on Platonism and Aristotelianism, astronomy and mathematics were taught. The ancient writers, particularly Homer, were standard reading for the students.

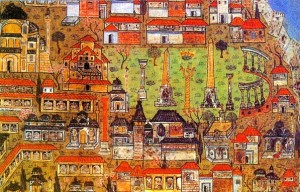

The most important scholars gathered in Constantinople, which because of the economic recovery was transformed into a commercial and cultural center, where products from every corner of the earth were traded and where the best craftsmen plied their trades. During the heyday of Macedonian dynasty (867-1056), the arts of the goldsmith, silversmith, painting of portable icons, monumental painting and mosaics were booming. New magnificent churches were built as well as monasteries, which also sustained charities (hospitals, schools, poor houses etc.). The palace acquired unimaginable luxury. Visitors were dazzled by its treasures and its size. In this period the population of the city exceeded 250.000, at a time when the biggest city of Western Europe had at most 20.000 residents. It is characteristic that the Vikings called it Miklagard, meaning “the great city,” while the Arabs often referred to it as Rumiyyat al-Kubra “the great city of the Romans.”

But while the capital city amassed two thirds of the wealth of known world, the empire languished and in the provinces separatist movements sprang up. At the beginnings of the 13th century the son of the deposed Emperor Isaac, Alexios IV, asked for help from the west in order that his father be restored to the throne, promising the Venetians financial rewards and the Pope the reunification of the Catholic and Orthodox churches.

Originally this building was thought to date from the 10th century, the years when Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos ruled, and later it was dated to the 13th century, in the reign of Constantine Palaiologos Porphyrogenitos. Porphyrogenitos means “born to the purple.” Purple was a color worn exclusively by emperors and the epithet was given to those emperors whose fathers were also emperors.

However, the masonry and the type of the building point to a later origin in the 14th century. The three-story building forms a trapezoidal enclosure, and is a heavily fortified citadel. The masonry consists of precisely cut stone block rows alternating with three rows of brick. The north and south walls of the palace has decorative brickwork in the shapes of diamonds, squares, and crosses. The interior of the building has not survived, but it still gives us important information about the imperial residence in the late Byzantine period.

As a result of this agreement, the knights of the 4th Crusade took a detour on their way to the Holy Land, besieged Constantinople, which they captured in 1203, restored Isaac and Alexios IV to the throne and withdrew, awaiting their remuneration. The sums were so immense that church treasures were divested and statues were melted in order to satisfy the requirement. When, after the death of Isaac and the murder of Alexios, the Crusaders understood that they could not expect any more money, they besieged the city and occupied it in April 1204.

For three days and three nights the Crusaders looted, slaughtered, raped and profaned according to the eyewitness historian Niketas Choniates. The Latin rule they established in Constantinople lasted until 1261, when Michael Palaiologos liberated the city. During the Latin occupation, the city declined and was systematically looted of precious works of art that were transferred to the West.

During the period of the Palaiologes that followed, great efforts were made to rebuild the capital and repatriate its population. The fortifications, the harbor, the palace and some churches were restored. Only a small number of new churches were built and these with money donated by senior officials. Some degree of prosperity was built, but the city also suffered natural disasters, such as earthquakes and pestilence. Just before the fall of 1453 and the victory of the Ottomans, the Imperial City was already weakened and boxed in, having lost the provinces of the empire. After 53 days of the Ottoman siege, the few defenders succumbed and the city surrendered on 29th May to the conquerors who engaged in looting, rapes and massacres for 3 days.

The Byzantine intellectuals who managed to flee to the West – mainly to Venice, Florence, Rome and other Italian cities – carried with them icons and manuscripts of works of ancient Greek writers. By this avenue ancient Greek language and learning survived and spread into the rest of Western Europe where it provided the germ seed of the Renaissance. Constantinople lived on as the capital city of the Ottoman Empire and has known days of luster, glory and growth until today, remaining one of the most charming cities of the world.

*The modern name of the city, İstanbul, derives from the Greek phrase “είς την πόλην” [eis tin polin – into the city]. Under Ottoman rule the city was known by both names in official records, depending on the context. İstanbul became the official name of the city after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire.

Virginia Albani, archaeologist, for the HFC.