The Byzantine-Arab conflicts that lasted from the seventh to the early eleventh century provide the context for Byzantine heroic poetry written in the vernacular Greek language. The most important and oldest of these works are the Song of Armouris and the epic romance Digenis Akrites.

The first of these works, the Song of Armouris, 197 lines of which survive, relates the deeds of the young Arestis as he battles against the Saracens on his way to Syria where his father, Armouris, is being held hostage. Arestis crosses the Euphrates and succeeds in defeating the Arab armies single-handed. Just one Arab survives the encounter, although he has lost a hand, and it is he who bears the news of the defeat to the Arab emir. Arestis threatens to slay the Arabs if they fail to release his father. The emir, alarmed by these developments, yields, releases Armouris and proposes that their respective children seal the deal in marriage. Although the plot is complex, the narrative is fast-moving and lively. And while the style is plain it has considerable descriptive power. The poem contains much of the formulaic texture of oral poetry.

By comparison, Digenis Akrites is a far more extensive narrative text, although it is not in a pure epic-heroic style. It survives in many manuscripts and versions. The oldest two versions are the Escorial version (=E, 1867 lines) and the Grottaferrata version (=G, 3749 lines), from the names of the libraries in which the respective manuscripts are held. Besides being descriptive of his dual origins (digenis: of dual birth, that is, Arab and Byzantine, Muslim and Christian), the name of the central hero of the tale also reveals something of his social role. The akrites of the Byzantine empire of this period were a military class responsible for safeguarding the frontier regions of the imperial territory from external enemies and freebooting adventurers who operated on the fringes of the empire.

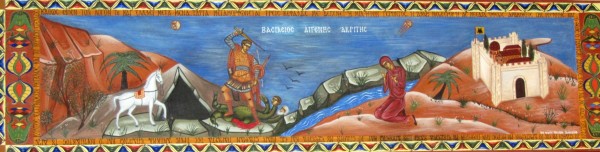

The work is comprised of two parts. In the first, the ‘Lay of the Emir’, which bears more obviously the characteristics of epic poetry, an Arab emir invades Cappadocia and carries off the daughter of a Byzantine general. The emir agrees to convert to Christianity for the sake of the daughter and resettle in ‘Romania’ (i.e. within Byzantine, ‘Roman’, territory) together with his people. The issue of their union is a son, Digenis Akrites. The second part of the work relates the development of the young hero and his superhuman feats of bravery and strength: like his father, he carries off the daughter of another Byzantine general and then marries her; he kills a dragon; he takes on the so-called apelates, a group of bandits, and then defeats their three leaders in single combat. No one, not even the amazingly strong Amazon Maximo, with whom he commits the sin of adultery, can match him. Having defeated all his enemies Digenis builds a luxurious palace by the Euphrates, where he ends his days peacefully.

While it should be noted that the form (or forms) in which Digenis Akrites has survived is not the product of oral composition, it has nevertheless retained a considerable number of features of its oral origins. The common core of the two versions preserved in the E and G manuscripts goes back to the twelfth century. The text of E appears to be closer to the original composition while G represents a version that is heavily marked by learned reworking. Both texts give enchanting descriptions of the life of the martial societies of the border regions of the empire, while in the figure of Digenis are concentrated the legends that had accumulated around local heroes. The Escorial version is the superior of the two in respect of the power and immediacy of the battle scenes and austerity of style. The epic descriptions of the mounted knights and battles are marked by drama, a swift pace and lively visual detail.

Judging by its style, the original composition of the Song of Armouris may well date to an earlier period that Digenis Akrites. The features of oral epic composition and a certain ‘archaic’ poetical economy found in Armouris are more marked. Likewise, there are important differences with regard to content: the encounters between Byzantines and Arabs appear to comprise the historical present of the poem; the narrative begins within the climate of military conflict and the shadow of Roman defeat at the hands of the Arabs (Armouris has already spent twelve years in captivity and his war horse has been grieving all this time in its stable) and it finishes with the emir’s proposal that Arestis become his son-in-law. Yet such an optimistic outcome (which on a symbolic level, through nuptial union, might represent the establishment of peace between the two peoples) is not recounted, and the tension between the Byzantine and Arab sides remains enigmatically unresolved. This stands in marked contrast with Digenis Akrites: while, in Digenis, the Arab incursions into Byzantine territory are the context within which the first part of the tale unfolds, the events in the part of the narrative concerning the family history of the central hero seem to be located (perhaps deliberately) beyond a climate of conflict. The reconciliation of the two peoples through the marriage of the leading figures of the tale and the triumph of Christianity over Islam, achieved through the conversion and reception of the emir and his people into Byzantine society, is the key theme of the first part of Digenis Akrites. The rest of the story unfolds against a background of peaceful coexistence of the two peoples.

The Byzantine Digenis continued to be read and enjoyed in later centuries, as the text survives in various versions dating to as late as the seventeenth century. The epic tale of Digenis Akrites gave rise also to a cycle of oral ‘akritic’ songs, some of which survived down to the twentieth century. In the later tradition Digenis is eventually defeated only by death, in the figure of Charos, after fierce single combat on ‘the marble threshing floors’.

Tina Lendari, reprinted from Greece: Books and Writers, courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.

An example of a contemporary, Epirotan folk song, retelling the story of Digenis Akrites:

What has happened to you, O Digenis, and now you want to die?

Rest yourselves, be seated and I’ll tell you all my story.

At Aravina’s mountain tops and Syra’s wooded valleys,

Where two don’t dare to walk nor three hold conversation,

But even fifty or a hundred are overcome with fear.

Yet, I alone did walk there, where there was only darkness.

Nights without any starlight, nights without a moon.

No one have I ever feared, no one from among the brave.

Now, there approached a man unshod, on foot he was and well-armed.

He had the markings of a lynx and lightning in his eyes.

He calls out to me to wrestle on a marble threshing floor

And whoever of the two will win, he can take the other’s soul.

So off they went and wrestled on a marble threshing floor.

Where Digenis strikes a blow, the blood makes a little channel.

Where Death strikes a blow, the blood makes a yawning pit.

Translation: Thomas J. Scotes in A Weft of Memory, Aristide D. Caratzas Publisher, New York, 2008.