“Today, after so many years, I still declare that Kontoglou’s work, in all its diverse entirety, has been of immense importance for our generation: it is one of those few creations to have enabled the forgotten voice of the east once more to be heard as it truly deserves, and to remind us of what may be the proper place for a culture destined by its own tradition to stand sovereign between the two great currents that passed across it; to weigh them, to judge them, to retain whatever of them was best, to digest them, and finally – having added a precious part of itself – to return them in a unique and incomparable synthesis.”

Odysseus Elytis, in Photis Kontoglou (Athens: Akritas Editions, 1995)

Photis Kontoglou – Reflections of Byzantium in the 20th Century

The Greek painter Photis Kontoglou was born in 1895 on the eastern side of the Aegean in the town of Ayvali, Asia Minor, the site of ancient Cydoniae in the land of Ionia, home of Greek poets and philosophers. His great love for Byzantium, the spirituality of the Orthodox Church and beauty of its art, led him to feel that his life’s task was to continue this long and great tradition that included both the era of the glory of the mighty Byzantine empire and the subsequent despondent centuries of subjugation and servitude. Kontoglou felt himself duty-bound to both his ancient predecessors and his contemporaries to uphold and revive this tradition that, in part due to Western influences, had been so casually neglected in the first hundred years’ existence of the modern Greek state (c.1830–1930), and to offer an authentic artistic language by which modern-day Hellenism could express itself.

He began his studies at the Athens School of Fine Art. Around the time of the outbreak of the Great War, however, he left Athens to journey through various European countries – France, Spain, and Belgium – working in various jobs as a casual laborer and even a miner. Born by the sea (he once wrote that “the briney sea lapped against my cradle and my hair was damp from its spray”), he was the son of a seaman who died while Kontoglou was still an infant. He grew up playing games in the sea and experiencing his own little nautical adventures, and thus had a passion for travel and the waves.

Kontoglou’s wanderings eventually brought him to Paris where he settled, “painting now again, writing a few pieces, and, above all, dreaming away my time”. From an early age, in fact, he had developed a talent for inventing fanciful stories for his friends and fellow pupils.

One of these “few pieces” was a brilliant novel he wrote in about 1920 entitled Pedro Cazas, a pirate story, in which the fantastical, and even the absurd, unfurl in a narrative both rugged and abrasive, smelling of the sea and the sunburnt bodies of the fearless corsairs, with a cut-throat balance between life and death.

The year 1922 marked a turning point in Greek history. In the wake of WWI, the Greeks of the Asia Minor littoral – inhabitants of the region for over two and a half thousand years – were uprooted and driven out by Turkish hordes, to find themselves refugees among their own people in Greece. And among them was the young artist and writer, Photis Kontoglou, who, after much hardship and many ordeals, arrived in Athens.

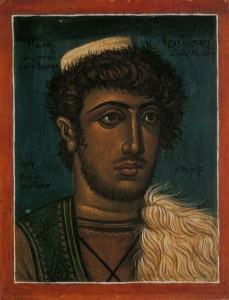

It was around this time that he visited the monastic community of Mount Athos in northern Greece, and it was here that his acquaintanceship with Byzantine art was first deepened. Astonished by its highly refined quality and expressive power, he was to write: “Never had I expected to come across an art so perfect within the churches of these monasteries”. Experiencing a kind of holy intoxication on Athos, he set about copying wall – paintings and icons and made it his task to unravel the secrets of Byzantine art, while at the same time he painted the Athos landscape, the monasteries and their monks, and wrote short tales brimming over with life and poetry. It was this art that offered Kontoglou a kind of consolation for the pain of being uprooted from the land of his birth.

From 1926 onwards he began to paint in the manner of his forbears in the age of the Byzantine empire, as well as of the later generations of Greeks living under the rule, primarily, of Ottoman sultans. The distinguishing features of this painting lie both in technique and style. Egg tempera (powdered pigments mixed with egg yolk) was applied to wooden panels in the case of portable icons, while wall paintings were executed by applying paint to the moist plaster of the wall (fresco technique). As for style, the foremost features are lack of perspective (and consequently the lack of a third dimension) in the works, the absence of a single light source, and the use not of tonal gradation, but of color contrasts that often serve to complement one another. Some of these aesthetic principles – though springing from different premises – coincided with the principles of modern art. In Byzantine art the use of color, for example, is often close to that of Impressionism.

On the other hand, the handling of the design, so that it becomes expressive of the message behind the figures while remaining indifferent to any anatomical accuracy, and of the landscapes and architectural features, likewise indifferent to naturalistic reality, seem to be close to the style of Expressionism. The intensity of color, which replaces the illusion created by tonal evocation of a third dimension, can reasonably be compared with the techniques of the Fauvist School. And the transcendence of unity of space and time has its equivalents in Surrealism. In a variety of ways, therefore, while Kontoglou adopted these techniques and styles of the past (without, it should be noted, slavishly copying them), he was at the same time approaching the modern aesthetic ideas that were shaking conventional academic standards and realism, and in this respect it is possible to see his sojourn in Paris as formative.

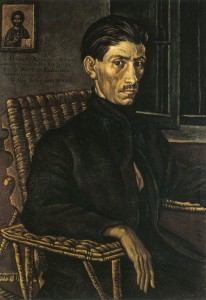

In his earlier works one can discern the influences of his European period, as well as his discovery of the work of El Greco, the famous late sixteenth-century Greek painter from Crete. The portrait of Nikolaos Chrysochoou (1924) demonstrates both this influence and the adoption of a number of key features of El Greco’s style. Yet another of these portraits, that of his compatriot, the writer Stratis Doukas (1923), is reminiscent of Gauguin, while his work “ The Old man of Kimolos” (1928) brings to mind Van Gogh.

But it was in murals – those he painted in his own home in 1932 – that Kontoglou was to bring his artistic visions to life, where he was to combine the techniques and style of the Byzantine tradition with his personal cultural and spiritual growth, as well as with the narrative of exotic journeys.

He painted the walls of his home from floor to ceiling according to the iconographic arrangements followed in the churches of the Orthodox East, but instead of religious subjects he presented medallions with ancient poets, artists and writers, as well as scenes from Africa, Dutch seafarers and colonists, the natives of Java, and more besides.

Three years later he has commissioned to paint a small chapel belonging to the Zaïmis family, close to Patras. This was the first time that he was presented with an opportunity to work in a church in precisely the same manner as his Greek Orthodox forbears had done. A number of other talented artists of the day – Demetrios Pelekasis, Spiros Vasileiou and Agenor Asteriadis – worked with Kontoglou in this revival of Byzantine art and the return of a traditional, Greek style, with its doctrinal character, to modern-day Orthodox churches

At the same time, Kontoglou, consistently applying his “Byzantine” style, painted subjects inspired by ancient literature (Ajax and Odysseus – 1934, Laocoon – 1936), or by contemporary figures (Hadji –Ustas Jordanoglou and his son Homer -1937), or by religious themes, though marked by a content that is either historical or beyond the constraints of time ( Greek Hostages – c. 1930).

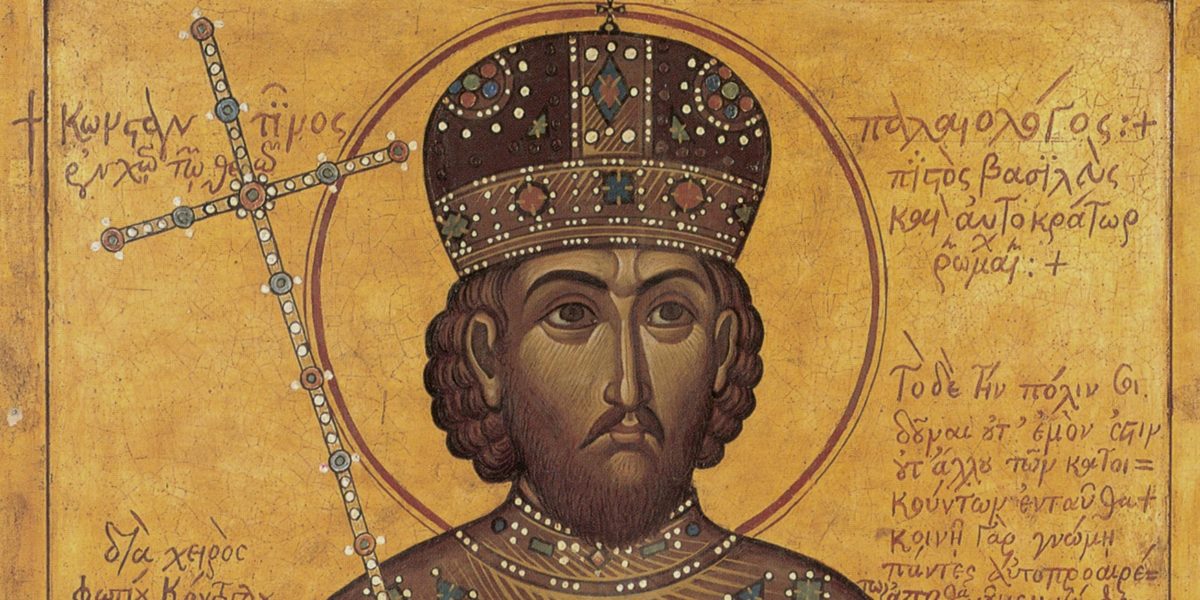

Shortly before the WWII he undertook a major commission: the decoration of the interior of the Athens City Hall with murals. This was an opportunity for him to make a striking statement. He was asked to paint scenes from Greek mythology and history, as well as events related more generally to Athens. The artistic language in which he was to present the subjects was the style he had used in churches and in other, smaller, paintings. He was to paint the heroes of classical mythology, such as Theseus, historical figures of antiquity, such as Philip and Alexander the Great, Byzantine emperors and commanders , and the freedom fighters of the Greek War of Independence of 1821, all in the Byzantine style, so that ancients and moderns took on the outward appearance of Byzantine saints. The entire history of the Greek people is turned into a kind of holy narrative, and the unity of its course – its continuity through the ordeals of the centuries – is rendered through artistic expression. In the murals in his home Kontoglou had narrated his own personal story and mythology. In the Athens City Hall he opened up his subject matter to Greek mythology, thereby acknowledging his debt to Hellenism past and present, and giving a response to the situation Hellenism now found itself in – contracted and introspective – because of the Asia Minor Catastrophe.

Greece had to resign itself to the fact that it could no longer sustain the “Great Idea” with its expansionist tendencies. As the Nobel poet George Seferis expressed it, Greece had now to gather in its dreams – to concentrate on itself and its potential, making use of its history, without dwelling on what might have been. In essence, this history constituted Greece’s real heritage: a rich source extending from Graecus and Hellene, lost in the mists of time, right up to the bard of the Hymn to Liberty, Dionysios Solomos (1798-1857), Greece’s national poet.

Above all, however, Kontoglou was to put his seal on the course of Orthodox ecclesiastical painting in the twentieth century, not just in Greece and the United States, but also in other, primarily Orthodox, countries, where his influence on their art is felt even today. In the Orthodox Churches of the former Soviet bloc and its communist satellites, there is a resurgence of interest in developing an authentic, Orthodox, artistic style, and young artists in these countries are looking to the work of Kontoglou for inspiration.

One may ask wherein lies the key to Kontoglou’s very special influence on ecclesiastical art? The answers are many: Firstly, the high artistic quality of his work, which goes hand in hand with living faith and spirituality. Secondly, the wide extent and volume of his work: after the WWII he painted around fifteen churches in Greece (churches in the United States were also decoratedwith his designs) and no less than five hundred portable icons. Thirdly, the many pupils and followers that he acquired, despite the fact that he never had any formal post as an academic or teacher. Fourthly, his work as a writer in general, and as an art specialist, for he wrote a two-volume work on the techniques and iconography of Byzantine painting entitled Ekphrasis tis Eikonographias (Description of Orthodox Iconography, Athens 1960), 220 years after a similar manual was written by Dionysios of Fourna, the Hermineia tis zographikis technis (explanation of the Art of Painting), no other comparable book having appeared in the intervening years. Lastly, and perhaps most importantly, he was the only person of his time to fully perceive the vital role that painting played within the Orthodox Church. A role that was at one and the same time theological, revelational, doctrinal, and didactic; a role that is linked with the very salvation of the believer. This is why he can be said not only to have fulfilled the role of an artist, but also – as the archbishop of Athens so succinctly put it at Kontoglou’s funeral (1965) – the role of a confessor.

Supremely gifted in many ways, Kontoglou labored hard to cultivate his talent, bringing forth exquisite works of art which he was to offer to the Greek Orthodox Church and to his country, and even, as we can gradually discern today, to the Orthodox world in general.

Nikos Zias, Professor of Art History, University of Athens, in the catalog for the exhibition of the same name organized by the HFC, 1997. Reprinted courtesy of the author.