In the 4th century, the Roman Empire was divided and the Eastern Roman Empire arose with Constantinople as the capital city. The official language of the Eastern Roman Empire was Latin, but Greek was the language spoken, the language of the Church and education. Latin is slowly displaced from every aspect of public life. Gradually, the word Romans came to mean ‘the Greeks of the Eastern Roman Empire’ and Romania was Byzantium.

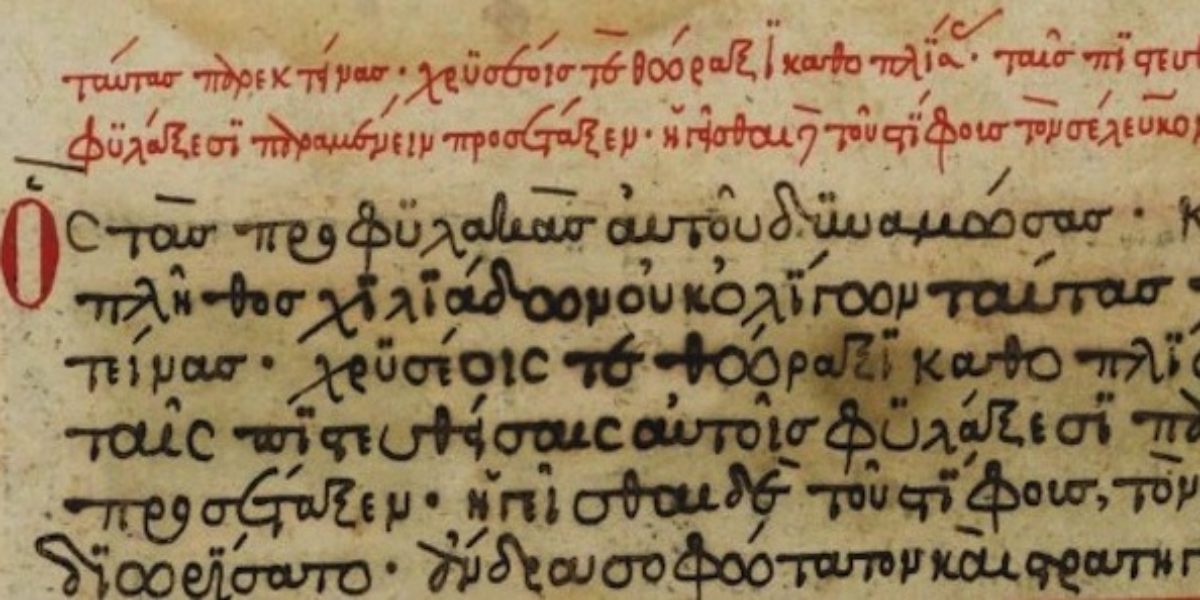

The written medieval Koine is archaic, while the spoken Koine is evolving, and the diglossia continues in the realm. The Byzantine scholars and writers employ as much of an atticizing language as they can, depending on their level of erudition. The Church Fathers, who up until the 4th century were using the Koine, are now atticizing more and more, and removing themselves from the common people. The atticizing dialect however helped proselytize the educated upper classes and helped combat heresies.

Because of the many centuries of co-existence with Latin, the Koine adopts many Latin words and phrases, especially terms of public life, and also makes use of many Latin productive suffixes.

The rift between the written and the spoken word continues to grow, since the spoken word continued to evolve. The innovations in phonetics and morphology are generalized, and new ones appear and gain more ground.

Until the 7th century popular texts on papyri still exist and facilitate the study of purely popular linguistic elements; later, the sources are exclusively scholarly. Because of diglossia, there is a gap in documentation until the 11th century. This is the period of the formation of Modern Greek but the written documents in the spoken language are sparse and consist in comments, which are improvised, ironic, teasing lines, and texts of few writers, who are more open to compromise with the spoken language. We have to wait until the 11th century for more texts employing the language of the people, although they are strewn with fossilized learned elements.

Athanasia Margoni, Centre for the Greek Language. For the HFC.