It remains an undisputed fact that what was called neoclassical architecture at the end of the 18th and the first part of the 19th centuries was an international style that was born as a response to the elegant and decorative court aesthetic movements of Baroque and Rococo. The rising social middle class sought new ethical and aesthetic models. These models were found in the ancient democracies of Athens and Rome.

In Greece, this style arrived via Germany. Let us not forget that Bavaria under the rule of King Ludwig was, in that period, among the most important centers of Neoclassicism. Nonetheless, the neoclassical style in Greece acquired its own dynamic and particularity, the main characteristics of which were its re-immersion in classical models, its wide acceptance, which exceeded the monumental structures and the well-heeled classes to reach the wide mass of the population and, finally, its long persistence, which runs to the interwar period.

That much given, I would like to emphasize that I am not an art historian, and consequently am not competent to enter into the aesthetic discussion as to what, and what is not, Neoclassical, what is Romantic and what is Neo-baroque. Nonetheless, it is my belief that we have become accustomed to speaking of the “Neoclassical Athens of the 19th Century” in a manner that I would say flattens these distinctions.

As already noted, between 1830 and 1833, before it was designated to be the capital, Athens already had significant construction activity. Characteristic buildings of this period are:

1. The house of Stamatis Dekozis-Vouros from Chios, in the district of Theater Plaza (today’s Klafthmonos Square), where Othon resided after his marriage, from February 1837 until the Royal Palace was completed in 1843. This dwelling was built in 1833-1834, based on the plan of the architects G. Luders and J. Hoffer, and today houses the Museum of the City of Athens, of the Vourou-Eutaxia Foundation.

2. The house of Kleanthis and Schaubert themselves, on Tholou St. in the Plaka. It is in fact a structure of the Ottoman period that was fundamentally restructured between 1831 and 1833, and that later housed the University (1837-1841). Today it houses the Museum of the University.

3. The house of the Austrian Ambassador Prokesch von Osten, on Feidiou St., built in 1835-1837, which housed the Greek Conservatory (1919) and today is abandoned, having undergone some changes of the first storey.

4. Finally, in the Aerides area, next to the Medresse, across from the Clocktower of Kyristou, the house of Lassanis, which was also built around 1830, or, in any case, before 1837, and which today houses the Museum of Musical Instruments.

Between the time of the drafting of the Kleanthis-Schaubert plan until final arrangements were made regarding the Royal Palace, that is from 1832 to January 1836, a significant number of important personages of New Athens (mainly Phanariotes) rushed to purchase lots, believing that the Royal Palace would be built as anticipated in the first two plans, that is, either at Omonia or at Keramikos, and to build in the broader Omonia district and along the Piraeus St. axis. Distinctive among the buildings are:

5. The two houses of Vlachoutzis, on Piraeus St, which were used as the first seat of the Regent. One of the two, the only one that has survived, housed, after one storey was added in 1845, the School of the Arts, later the Polytechnic (1837-1872), subsequently the Athens Conservatory and, today, the Drama School of the National Theatre.

6. The house of Provelengios, very likely once the house of Botsaris, on the corner of Keramikou and Myllerou St.

7. The mansion, or better the compound, of Katakouzinos, also on Myllerou St., (that remained half-completed when the site of the Royal Palace was finalized).

Finally, during the same period, the first state buildings of Athens made their appearance. For example:

8. The Royal Printing Office on Stadiou St., between Santaroza and Arsaki streets, based on the plans of J. Hoffer, and built between 1834 and 1835. It originally housed the Printing Office (until 1906), and subsequently the Athens Court of First Instance (until 1984). It survived, with serious alterations from 1931-32.

9. The Mint on the Stadiou St. side of Theatre Square (that is, Klafthmonos), which was built in 1835, mostly likely on a plan by Schaubert, and which later (1884) housed the Finance Ministry, with the addition of another storey. It was torn down in 1940.

Notably almost none of the public buildings were built where the city plans had anticipated, but instead, for the most part, on whatever public lands were available. Regarding all of these early buildings, it is obvious that of least concern in their construction was whether they adhered to some style, neoclassical or otherwise. They were modest two-storey structures, with simple lines, and not particularly elegant. Nonetheless, a classical discipline of form and in the handling of space is discernable.

In the meantime, of course, the first structures appeared in which the architectural order is more emphatically manifest.

Characteristic examples are:

10. The villa of the British Admiral Malcolm (Admiral Codrington’s replacement in the command of the British Fleet in the Mediterranean), which was built by Kleanthis and Schaubert in 1832 in the then rural Kypseli dictrict, “half an hour from Athens,” according to Ross, near Agia Zoni. It later housed the French Embassy.

11. The house of Ambrosios Rallis on Klafthmonos Square, which was built in 1835, also by Kleanthis. It later housed the British Embassy until its demolition in 1938.

12. Finally, the house of the German philhellene Heinrich Treiber, also built in 1837, on the corner of Ermou and Agion Asomaton streets, which at one point housed the Poorhouse (1865). It does not exist today.

At the same time, the construction of other buildings began, such as:

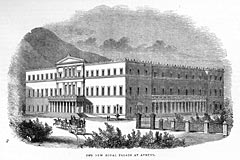

13. The Royal Palace, based on the plan, as already noted, of von Gaertner (1836-1843).

14. The City, so-called Civic Hospital (1836-1858), which today houses the City of Athens Cultural Center.

15. The University, based on the plan of Christian Hansen (1839-1864).

16. The Gennadios house in 1845, on Akademias St., where for a short time the French Archeological School was housed (1846-56), and later various schools, such as the Ionian School and the Economic High School, which was torn down in 1980.

17. Finally, the Arsakion Girls’ School, in its initial form, by Lysandros Kaftantzoglou (1846-1852).

The central buildings of the University of Athens are characterized by their rigorous composition, based on balance, simple geometric forms, specific templates, homogeneity of materials, antique style, with a tri-partite ordering of facades that is stressed by the pediment, without, however, exaggerated decorative elements.

This Athens is not particularly well-known to us, since laid over it was the later, so-called Eclectic Athens of the second half of the 19th Century—briefly put, the Athens of Ziller. This later architectural order is characterized by a continually increasing search for “artful” decorativeness, which quickly became stereotypical and widespread: “anthemia” (palmettes), antefixes, statues, birds and flowerpots, which were sold readymade at construction materials depots. The tendency towards making an impression led to the asymmetrical organization of space, as, for instance, in the case of the Stathatos Mansion.

The degree to which this neo-Baroque style is still Neoclassicism or not is for me unclear, but the matter is of little relevance for the approach I am taking. I agree completely on this point with the observation of Elias Mykoniatis, that “chronological boundaries, when talking about architectural orders, are often fluid, and when accuracy is a patent intention, often have little value from a historical standpoint. In architecture, each decade has its own thematic ideals and its own mixture of styles,” and, to make matters more complicated, he adds that earlier styles often survive unchanged for a long time alongside the new styles that make their appearance.

What is of interest for our historical approach is that research into the material remains of Athens be conducted systematically. In such an approach, the study of architectural styles takes leave of aesthetics to become a tool for understanding the historical development of the City’s structural foundation, its social structure and its functional activities. In such an enterprise, it is necessary to free ourselves from the study of a few well-known structures, which traps us into believing that little else has survived.

At least a third of the buildings on Aiolou Street today are still the buildings of the 19th century, often hidden beneath metallic additions and store windows. The same applies to Metropoleos and Ermou streets, along with dozens of other streets in the historic center, and not there alone. On streets considered to have been utterly transformed, such as Patision, Acharnon or Tritis Septemvriou streets, and in districts such as Vathi Square and Agios Pavlos, many significant buildings of the 19th century still exist. The yard of today’s Asylon Aniaton in Kypseli hides the 1832 Villa of Admiral Malcolm, of which we spoke earlier.

As I and my colleagues prepared the papers for the present volume, we were led once more to the conclusion, which sounds, perhaps, oxymoronic: that finally the Athens of Pericles is better known to us than the Athens of Kolettis and Trikoupis. What remains, then, is to focus our interest and become more systematic in researching our city. Possibly by knowing it better, we can love it more, and perhaps abuse it less.

Leonidas Kallivretakis, Historian, Research Director, National Hellenic Research Foundation.

Reprinted courtesy of the National Hellenic Research Foundation – EIE where you can read much more about the architectural history of the city.