– The Greek Blues

Ever since Sappho “loved and sang,” nine-time rhythms have been found on the shores of Asia Minor, in the islands of the eastern Aegean, and in the Dodecanese. Today they are represented by the 9/4 beat of the zeibékikos and the 9/8 beat of the karsilamás.

These two rhythms, in their several variants, and the 2/4 time of the khasápikos are also prevalent in the urban, popular music of the Aegean, which since the final decades of the 19th century has spread from its epicenter, Smyrna, to all harbor towns and so created that marvelous tradition of the rebetiko song.

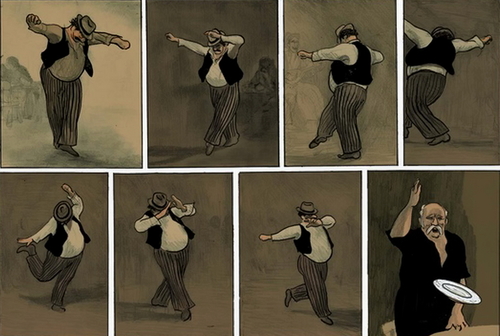

Indeed, if we exclude its off-shoot on the mainland of Greece (represented for the most part by Tsitsanis’ songs), rebetiko was born and matured by the waters of the Aegean, giving expression to the aspirations and woes of the lower and middle classes in the harbor towns. Looking into the background of its outstanding figures, we see that all of them – composers, vocalists, musicians, and even those who made a career in the Greek recording studios in the US are connected with the islands and seaboard of the Aegean: Vangelis and Angela Papazoglou, Markos Vamvakaris, Maria Papangika, Rita Abatzi, Antonis Delgas and others. The list is extraordinarily long. The Aegean Sea rebetiko is a product of the taverns, coffee houses, and cafes-aman (derived from “cafes chantants”). “The taverns of Smyrna and other ports are constantly filled with men dancing, drinking, and singing; they even manage to find a little space on the decks of their vessels to indulge their passion for dancing” – so wrote the traveller Batholdy at the beginning of the 19th century.

The rebetiko maintained all the characteristics of a genuine popular creation, especially during its first two phases (up to 1940), and, more importantly, clearly proves once again that capacity for assimilation and regeneration in the face of foreign influences, which has ever distinguished Aegean civilization with its unique adaptability to the social circumstances of the day.

As early as 1702 Tournefort observed that in Smyrna “the taverns were open all hours of the day and night. Inside they played music, ate wholesome food and danced a la Franka, a la Greca, a la Turca …” The meeting of East and West in the territory of the Aegean, to which reference has already been made, found one of its finest expressions in rebetiko songs and dances. The harbour-towns were the places where Italian, French, Rumanian, Serbian, Turkish, Persian, Armenian, and Romany influences were filtered through the age-long musical tradition of the Aegean. In the narrow waters around Smyrna old Aegean sea ballads mingled with Italian canzonettas, French sea chanties, Rumanian hora (a dance type), Serbian airs, and Turkish sarkia (a song type). Greek musicians playing in cafes-aman before an audience that represented all the peoples in the eastern Mediterranean accompanied Armenian singers and gypsy dancers.

Transferred to the grooves of gramophone records, the result is startlingly articulate. It is the rebetiko that works wonders. It combines all these influences in a music destined to take its place in Aegean musical tradition and to sustain it in keeping with its character.

To illustrate, the first rebetiko ever recorded was recorded by Tetos Demetriades in 1927 in New York, a song called Misirlou and since used in Pulp Fiction and covered by various artists including The Blackeyed Peas.

Rebetiko is a music that rests firmly on the melodic and poetic structure of Greek demotic song and yet which never hesitates to make bold and imaginative use, on the one hand, of the harmonic language of the West and, on the other, of the artifices and guiles of the East with every variety of colour and, one might even say, scent. In his autobiography Markos Vamvakaris movingly describes the island festivities and feastings in Syros at which he accompanied his father, playing the tsambouna, on the toumbaki. Later on he took up the bouzouki (a kind of chordophone) and baglamas (a short-necked bouzouki), instruments severely condemned by critics of the rebetiko even though they are descended from a family that includes the ancient Greek pandoura and trichordon, the Byzantine thambouras, and the tamboura played by warriors fighting in the 1821 War of Independence.

The rich musical tradition of Greeks living on the coasts of Asia Minor (including that of the Smyrniot rebetiko) was transferred to all those places to which the refugees fled after the 1922 disaster. There it was grafted on to local musical traditions with all the ingenuity of the Greeks of Anatolia and with the same spirit of nostalgia and inner intensity that migrations around these waters have concealed from the time of Odysseus.

Dr. Lambros Liavas, Museum of Musical Instruments, reprinted from Music in The Aegean, courtesy of the Hellenic Ministry of Culture.